The 2024 presidential election is intensifying discussions around the role of social media in influencing public opinion and voter behavior.

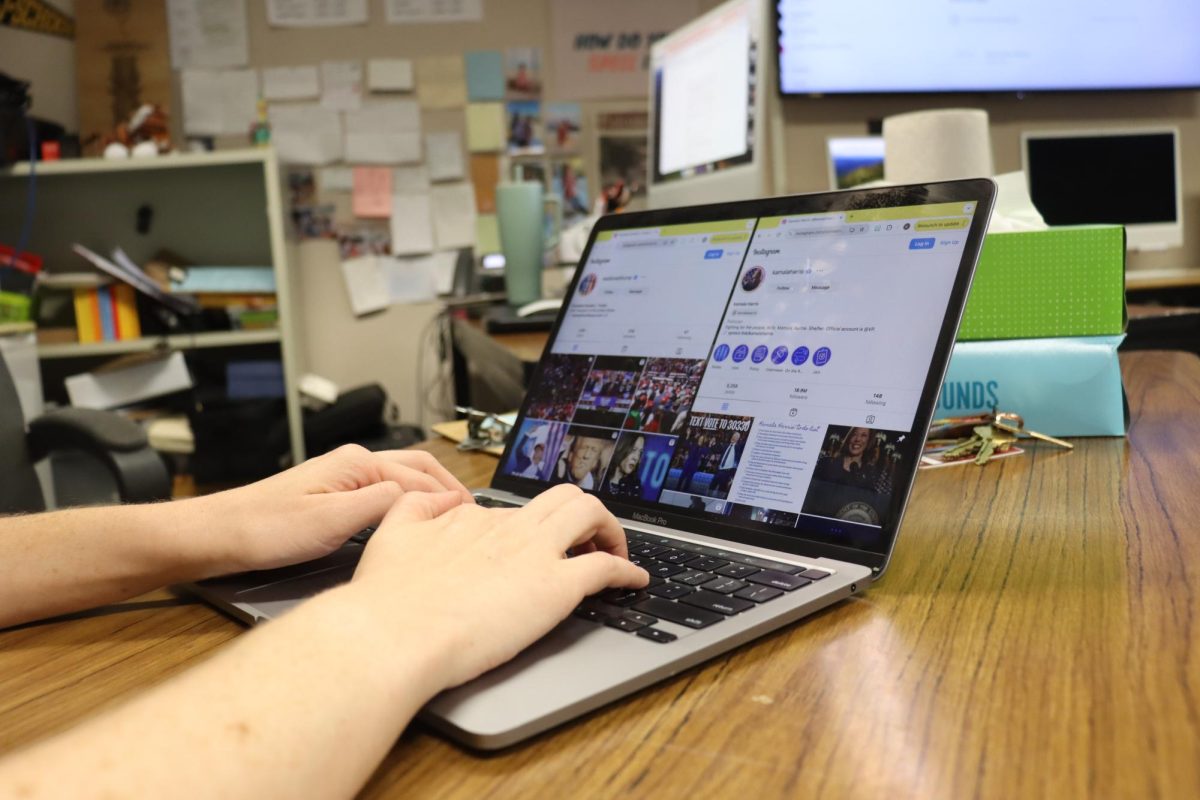

Presidential candidates Kamala Harris and Donald Trump use mainstream platforms like X (Harris, Trump), Facebook (Harris, Trump), TikTok (Harris, Trump) and Instagram (Harris, Trump) to engage with social media user bases. AP Government and Sociology teacher Jack Milner noted the double-edged nature of social media for candidates.

“If it comes off [tone-deaf], you can hurt yourself, but at the same time, it’s a great way to mass reach millions of people of different backgrounds and ethnicities and socioeconomic statuses,” Milner said.

Milner downloaded X and other social media platforms this summer to follow both presidential and vice presidential candidates, especially in relation to the curriculum he teaches. However, he ended up deleting them this school year.

“I wanted to get that kind of media in terms of … what political activity is going on there,” Milner said. “I would get some stuff from their actual campaign or social media teams, but it was also very hard to differentiate between if it was from the campaign, from the actual horse’s mouth, or the elephant’s mouth, or from fake accounts that were purely for spectacle, purely for memes.”

Milner witnessed social media’s evolution through earlier elections, describing Instagram in 2012 as “not very political,” something that has not held up to present day.

“2016 was where everything kind of went crazy, and all of a sudden, now we’re in 2024, and kids and young adults are so active on social media, that’s how you connect out,” Milner said. “I think it’s generally become more extreme, and you find yourself in the echo chamber of whatever partisan group that you want. There’s an algorithm.”

While Milner is noticing the increasing polarization on social media, as a teacher, he does not see this with his AP Government students.

“My AP Government students seem to just have such a well-rounded, calm demeanor about the whole thing,” Milner said. “When I just mentioned [Trump’s] name, I used to see the cringes and the disgust on people’s faces; now I don’t see that as much even though it’s still so divided.”

Zachary Dawson (12), vice president of TP Political Union/Get Out and Vote Club, agrees with Milner’s observations on polarization, noting that social media has become “a source of both information and disinformation.”

“[Social media is] playing a bigger role in every election, particularly among young people,” Dawson said. “I don’t think it’s great for the unity of the country, because I think the algorithm divides people.”

Jack Sheehy (12), co-president of the Political Club, attributes these echo chambers to the basis of social media.

“I think one of the big issues with social media is it’s a technology,” Sheehy said. “It’s got the same thing with generative design, where you’re trying to find the quickest path through. They’re going to keep pushing what you’ve liked and they’ll drift away from what you didn’t like … that’s how we’ve designed computers since the very beginning, is to find the quickest way to solve the problem.”

Besides the presence of algorithms, Sheehy attributes changes in perception of the candidates through social media to the people who run large media corporations, using X as an example.

“Large corporations like X, Facebook and Instagram are now almost picking sides, and so they’re catering their platforms to certain candidates in promoting their views on the platform,” Sheehy said.

Milner also mentioned this possibility.

“There’s the sentiment that Twitter kind of had a hand … at least Facebook too, had this hand in removing information that could have swayed the election in 2020,” Milner said.

A recent study explored the creation of social media echo chambers through politically biased content moderation and removal. In a Q&A with University of Michigan News, Justin Huang, Assistant Professor of Marketing at University of Michigan Ross School of Business and one of the study’s authors, emphasized that “biased content moderation is not limited to any one side,” and is present in all major social media platforms.

However, Sheehy also mentioned the benefits of social media’s role in the 2024 election.

“I think [social media] helped us progress very far from the days when you were sending electors to Washington, D.C. and they were going by horse and buggy,” Sheehy said. “Things are being kept on second-by second notice … It’s kept people very in the loop, it’s helped promote interest in the election and in voting, especially as we see more behind the scenes of the people and their policies … it’s the [candidate], their character, their backstory, how they got here … and that can affect how [people] vote.”

A key component of social media influence in the 2024 election is political memes, some of which include Trump’s time working at McDonald’s and Harris’ “coconut tree” line.

“I think [memes] are a very good way to … simplify these very complex issues and make them more digestible for younger audiences,” Sheehy said.

While agreeing in part, Dawson acknowledged the risks of using memes.

“I think memes can be a useful way to bring attention to some things, but also, I think there’s a danger in playing down certain issues and kind of making a joke of them, or making a joke of certain people through memes,” Dawson said. “I think it gets dangerous once you start degrading people, or turning people into a joke rather than approaching the issues.”

According to Dawson, a newer development with media use falls in the adjacent realm of podcasts, with Trump going on “The Joe Rogan Experience” and Harris going on Alex Cooper’s “Call Her Daddy.”

Additionally, while campaign ads have long been an integral part of elections and politics, Sheehy observed an “interesting balance” in ads for both parties, noting a difference in “the amount of quality and time [put into] different ads.”

“A lot of the Trump campaign’s ads I’ve noticed are a little more ramshackle, or just a video of him or one of his supporters saying some stuff, while Harris’ are more focused, have more graphics, more interviews, focused on informing people,” Sheehy said. “Trump’s are more just his image.”

Candidates also use platforms differently. In particular, Trump owns his own platform, Truth Social — marketed as “America’s ‘Big Tent’ social media platform” — where Harris’s campaign also has an account.

“Trump has his truth social, that’s kind of his platform … and I think one of the big things, particularly with Trump, is he uses social media almost as kind of just like a brain dump,” Dawson said. “He kind of puts what he’s thinking on there, those random all-caps tweets … whereas with Kamala Harris, it’s typically more like a more refined press release.”

One notable shift in the 2024 election cycle relates to how candidates speak about each other, especially on social media. Milner observes a distinct change in the dynamics of this year’s election.

“Back in the day, Obama and Romney in 2012 were shaking hands and they’re really chummy,” Milner said. “Not that it wasn’t super cut-throat back then, but now it’s become this. They’re pretty brutal … I do think it’s extreme, but it’s 50-50, so it’s going to be won by a few thousand votes, and so [it’s about] if you can push those few thousand over the edge.”

The increasingly personal nature of these exchanges has also impacted public perception, according to Sheehy.

“A lot of us view these large political figures as almost supermodels and such,” Sheehy said. “And so to hear them talking about each other in derogatory or insulting ways … is very influential on people who may not understand what topics they’re speaking about … they’ll lose the nuances to it.”

Dawson believes that use of disparaging comments has been “more part of the political discourse than it was previously,” both “on and off social media.” While Dawson believes disparaging comments are “kind of part of [Trump’s] brand,” he pointed out that use of such comments does not just apply to one side of the election, as “some of Kamala Harris’s rhetoric, although this isn’t covered as much, can also be disparaging.”

“I think social media only serves to amplify those comments, and they get put through editing, through various supporters, they get spun, they have captions attached,” Dawson said. “That kind of just changes people’s view on things, and ultimately ends up dividing people.”