Kindergartners are known to be a handful, expressing a variety of behaviors that require the diverse skillset of a teacher. However, when Lauren Chambers taught a high-needs student in her own classroom, she learned that she would have to adapt, and with that, eventually grew into her career in psychology. With the help of a summoned school psychologist, she became inspired by the work, leading her to where she is now: working as a data-driven school psychologist at TPHS.

Chambers works in the school’s special education department. Having worked within SDUHSD since 2017 (starting with her position as a school psychologist at Pacific Trails Middle School), she views her role as one that “levels the playing field” regarding the destigmatization of mental health on campuses within the district.

“My job is to evaluate kids to see if they need special education services and support, or if they already have those supports,” Chambers said. “I have to see if we are supporting them in the best way possible.”

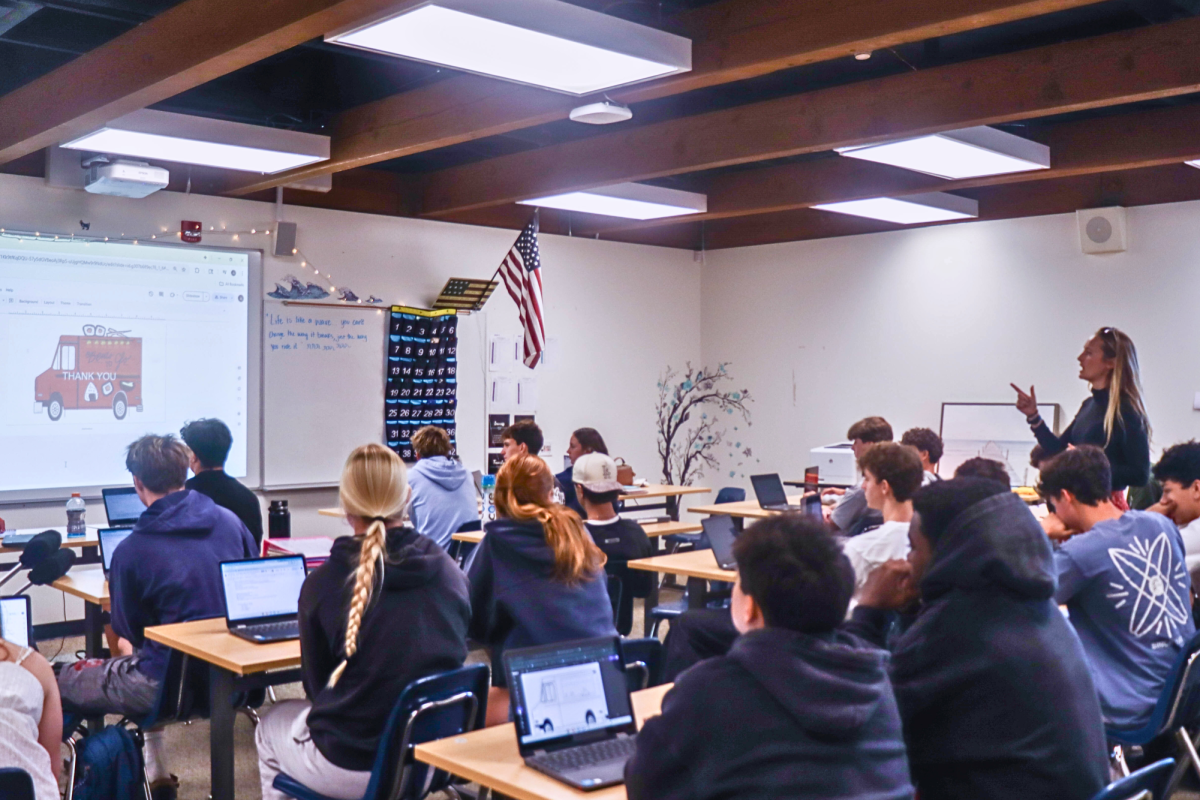

Instead of working in a position like that of a counselor, who sees students day-to-day, Chambers’ office can be found in the administration building, where she takes a more empirical approach to helping students.

“[My] job is to make data based decisions, so if [I] don’t know something, [I] collect data, whether that’s observing [students] in the classroom or doing really specific tasks,” Chambers said. “My job is to kind of dive into all areas of suspected disability. If somebody makes some kind of comment, like, ‘Oh, this person might not have a good memory,’ then I’m gonna dive in, like, ‘Well, is it visual memory? Is it auditory memory? Is it their delayed memory?’”

Marlo Roberts (11), co-president of the Best Buddies club, agrees that Chambers’ role will add something positive to the mental health community at the school, as her data will balance out with the personalized connections the club has with the student population. Also run by Harper Kelley (12) and Jacob Cava (12), the Best Buddies club focuses on fostering unity with students that have cognitive and developmental disabilities.

“We need not only buddies to have individualized attention [from our club members and adult staff], but we also need the students on campus that are battling their own internal issues to have that individualized assistance, which is what professionals like Chambers would offer,” Roberts said.

Focusing on Chambers’ reliance on data to carry out her daily tasks, Roberts noted how this can be used to aid those who truly need it.

“We could use data to look at the 10% who say they are not happy during the bi-annual surveys and ask, ‘Who are these students? What class do they belong to? What clubs do they belong to? What classes are they taking?’ and assess from there and determine if we can improve the functioning body of Torrey Pines as a whole,” Roberts said. “We should really be looking at what we’re doing wrong so that we can fractionalize our problems. If we gather data from those who are struggling or take the opportunity to reach out via these forms, maybe we can find the people that do need help, rather than just assuming that the people who need help will get help on their own accord.”

Kelley also noted how Chambers’ presence on campus will be beneficial for the community, as her data-driven approach will reduce generalized labels within the mental health community.

“[Her role] could benefit students because it’s less centered on stereotypes and more about observation and data,” Kelley said. “It’s more … scientific and will help create better … ways to help students.”

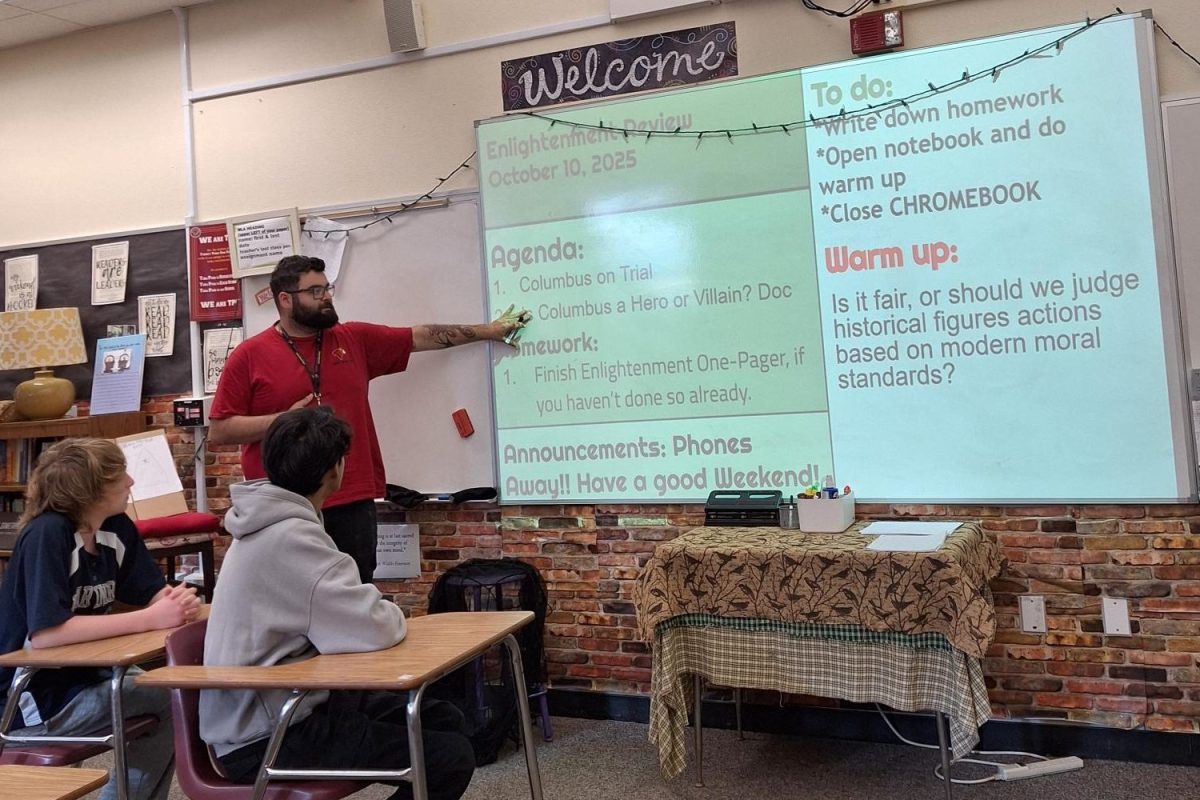

Another factor within Chambers’ job, unlike other faculty on-site, is that her presence on campus is only on Mondays and Thursdays. As a district staff member for over 14 years, Chambers takes on a flexible role within SDUHSD.

“My job kind of takes me all over the place — I have other duties within the district too, so I’m not always here,” Chambers said. “For instance, the school psychologists meet one day a month, so that takes me off campus during lunchtime once a month.”

Even though Chambers follows the more data-driven approach, she still occasionally meets with students in person, or visits another campus for an allotted amount of time until she is cleared to leave.

“Sometimes [I] have to go to non-public settings to do assessments,” Chambers said. “If there’s some kind of major need going on [at a different location], if there’s some kind of crisis, [I] might get pulled to a different school. If somebody’s out on maternity, [I] might get pulled to a different school to help. So there could be all kinds of reasons why [I’m] all over the place.”

No matter where she is stationed, Chambers remains reminiscent of how she got to her position at the school.

As a new face on campus, Chambers is most excited to be able to recognize faces from her past teachings and evaluations.

“I have been working at [Pacific Trails Middle School] for years and years, so sometimes I just see students from the past,” Chambers said. “Sometimes I’ll go to a classroom and I’ll see somebody that I haven’t seen in a couple years, and it’s like, ‘Oh my gosh, they’re tall now, and they’re learning math and they’re doing great.’ So that’s really fun and awesome to see.”

As a student who works directly with special education students in her club, Kelley not only sees collecting data individually as a positive step for our student population, but as a way of increasing knowledge in the mental health community.

“A lot of people don’t take the time to go and talk with [students in our special education program] or connect with them,” Kelley said. “So I think if we’re raising awareness about that data that we collect, more people would be aware of the [mental health] community and what it stands for: equity and inclusion.”