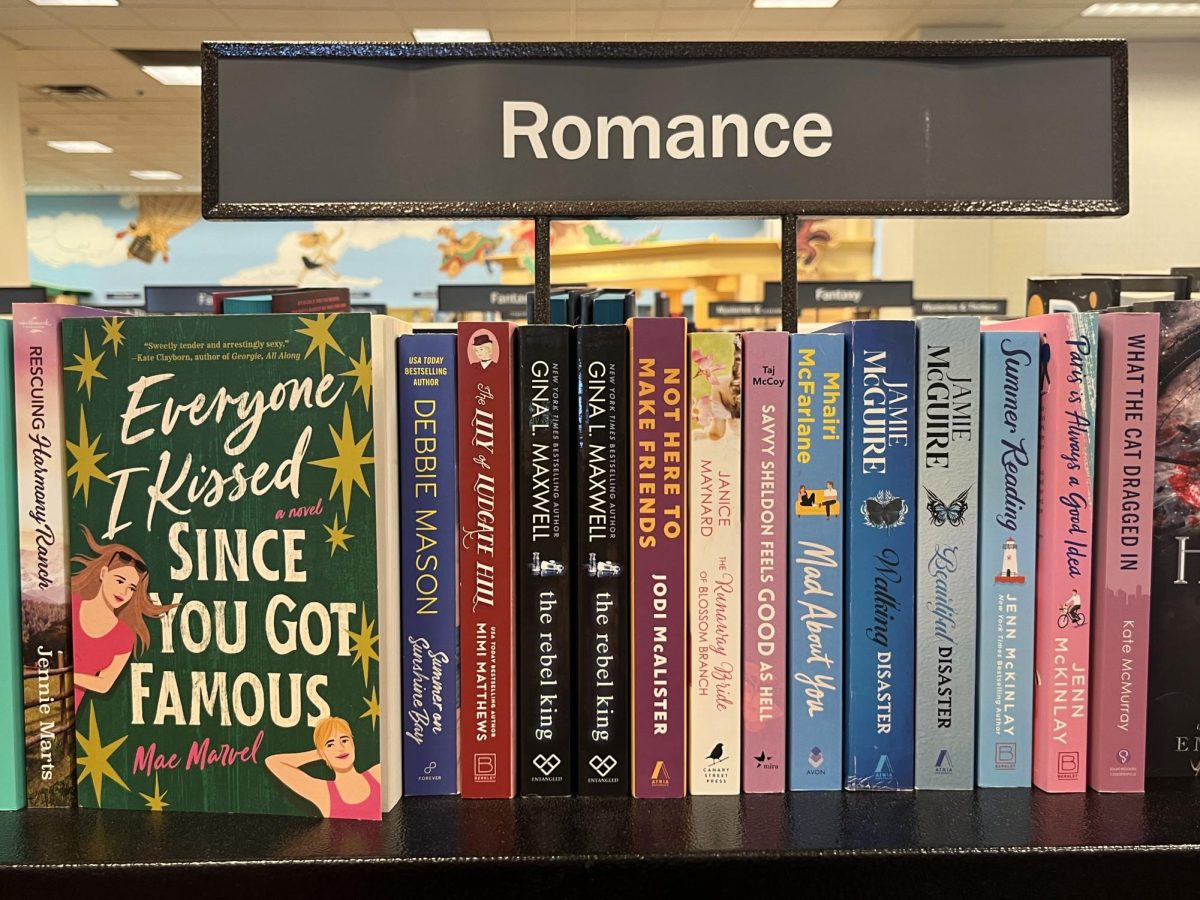

Since its rise during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, “BookTok,” a popular TikTok community interface where readers can interact and share their favorite novels (primarily romance novels), has since stirred the debate over which fictional romance trope is the best. Whether it be friends-to-lovers, grumpy/sunshine or academic rivals, it is clear that men and women have played entirely separate roles in fiction throughout literary history — roles that have developed for the worse among today’s audience.

The Female Protagonist Dilemma

In this day and age when women’s rights are constantly in the spotlight, it’s even more crucial for authors to depict female leads in a powerful way, while also ensuring the content around the character remains in a healthy balance. Unfortunately, when it comes to well-written female protagonists, it can be a bit of a hit-or-miss. Recently, though, it seems fiction has adopted a switch: from what once was the goal of portraying women as housewives and symbols for innocence, purity and victimhood, now illustrates the goal of writing women as independent heroines that represent strength, intelligence and curiosity. On paper, all of that sounds great; changing the stigmas of early female portrayal is vital to a more progressive and accepting society. And yet, the extent to which these female protagonists are mass-produced, practically copy-and-paste versions of each other, begs the question: How truly applicable is the “girlboss” trope to modern women?

Honestly, it isn’t. Not only are female protagonists written from the same formula, but their authors compose them to the extreme, so much so that some may view them as unlikeable or abrasive. Perhaps it is because of the many years that women have been subjected to systemic oppression that authors feel the need to write their female leads as independent and goal-oriented, and while that effort is noted, readers might interpret such characters as controlling or apathetic when said traits are taken to the extremes.

But the underlying issue is that even with all of these powerful female characters making their debut, they are still driven by the presence of sexism.

For centuries, women have been illustrated in novels as meek and fragile, an object to be dealt with or a trophy to be won by their male counterparts. One such instance of this lay in the story of “Jane Eyre,” an 1847 classic romance novel by Charlotte Bronte, where Victorian women are considered as the subservient sex, their purpose surrounding their families and husbands. Similar are 1811 and 1868 novels “Sense and Sensibility” and “Little Women,” by Jane Austen and Louisa May Alcotta, respectively; in these novels, there is a heavy concentration on women taking a more wifely or maternal role, remaining objectified and inferior to the male gaze in order to attain security in marriage. Since then, women have woken up, and in protest, it is in some authors’ best interests to write their fantasy heroines into the world as a living, breathing symbol for justice. However, all of this could be interpreted strictly as a retaliation against men’s centuries-long coddling of women. These toxic trends of female protagonists are not at the fault of women or men, but of the societal expectations implemented centuries prior, dealing both with toxic masculinity and damsels in distress.

Red-Flag Relationships

Unoriginal and vastly perpetuated, the classic “damsel in distress” and “knight in shining armor” trope displays nothing but blatant sexism. It has also been the starting point to toxic character dynamics that we see today. From Andromeda’s role in Ancient Greek mythology to Lily Bloom’s perspective in the 2016 novel by Colleen Hoover, “It Ends With Us,” both show accounts of female protagonists being damsels in distress (even though Bloom chose herself and her daughter in the end, she consistently ran to a prominent male figure from her past, Atlas Corrigan, throughout the novel).

To put it simply, a woman being “saved” by her male partner tends to be a toxic scenario by nature as it eliminates the woman’s autonomy in the situation. Authors often romanticize ideas that would be dangerous in real life, such as a man’s jealousy over a woman escalating to physical violence (usually with other men) in order to “defend her honor.” By instating values such as these into readers’ minds, authors reinforce the idea that these toxic relationship dynamics are healthy, when they most certainly are not.

Some may argue that if an instance such as the one described above were to appear in a novel, its presence would be appreciated because it shows how women are actually supported by their male partners and his ability to shield her from the violence or arrogance that other men may depict in that scenario. This is wrong. For a male partner to “protect” his female partner from toxic masculinity is a further perpetuation of toxic masculinity itself, as he is then adopting more of a “savior complex.” Additionally, if the relationship itself is so steady, why does the man never get saved? In real life, a male partner “protecting” his female partner from another man may seem noble, but when this type of support always comes the man and never the woman, it can unknowingly perpetuate the idea that men must be unwavering heroes, an idea that again stems from toxic masculinity. Healthy relationships elicit balance, and yet authors consistently portray women as weak and vulnerable compared to their male counterparts.

Any person can write their fantasies on paper, but composing a novel with strong, likable protagonists, as well as both realistic and healthy tropes within relationships has proven a struggle for even the most esteemed authors. Even though there most certainly are some well-written women and relationships in the world beyond BookTok, it may still be a time before more popular authors can get it right.