Jaewon Jang

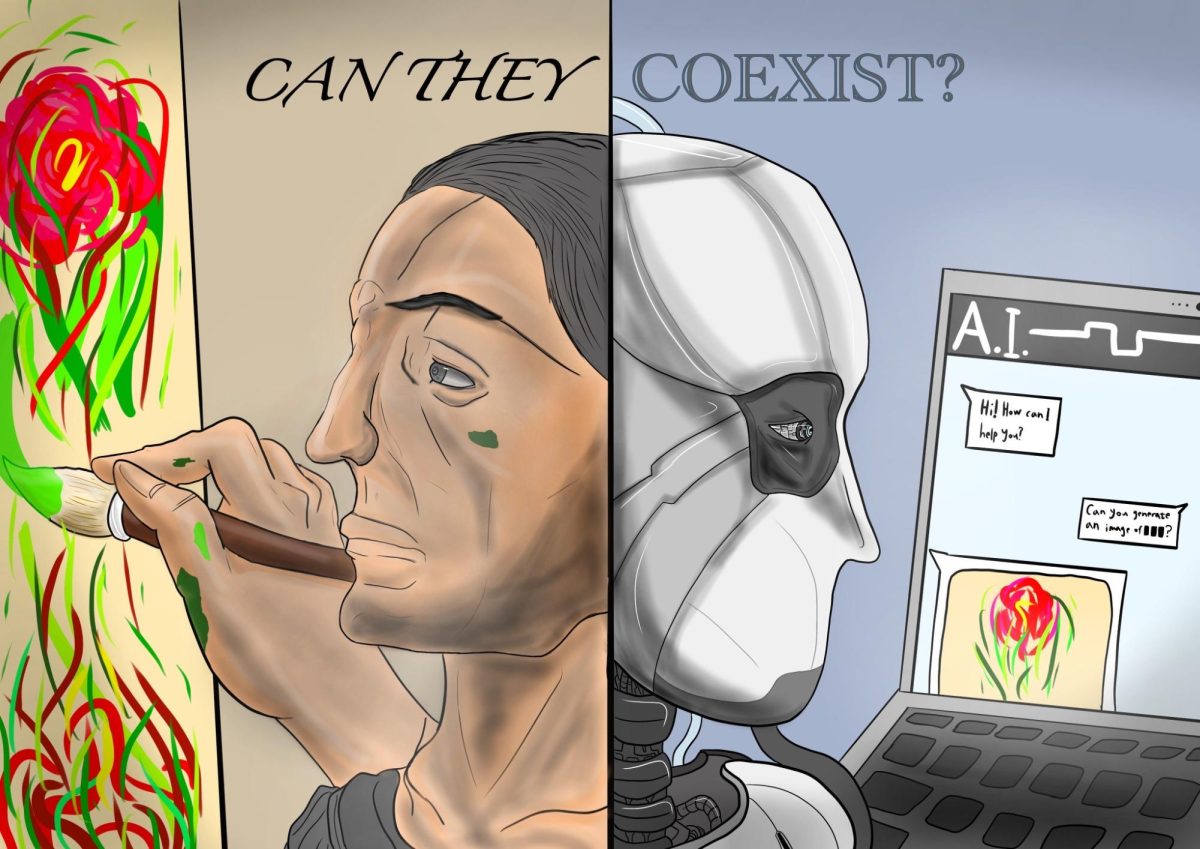

With the introduction of generative AI, the nature and creativity of artistic endeavors may be threatened. Could human-created art and AI generated art coexist?

In the 1970s, a curious new artist emerged. It drew with lines that were shaky and organic, yet purposeful, almost methodical. The artist’s name was AARON. But AARON wasn’t human. It was a software program created by painter Harold Cohen, now regarded as one of the earliest examples of AI art.

Cohen had fascinating, often paradoxical takes on his creation. “A computer program is not a human being,” he stated, describing it as incapable of learning through observation, or perceiving aesthetics and style. It was a strange assistant that lacked cognition, existing in a liminal space between a tool and an intelligent mind. Unlike today’s AI services, AARON did not pull from massive online datasets or use models mimicking human intelligence. It followed hand-coded rules, up to 4,000 solely to draw a head. Still, reflecting on the implications of his work, Cohen concluded, “we are living on the crest of a cultural shock-wave … which thrusts a new kind of entity into our world: something less than human … but … capable of many of the higher intellectual functions we have supposed to be uniquely human.”

As Cohen foresaw, the progression of AI research in the past five decades has shattered any convenient shorthand for distinguishing between machine and human intelligence. Today’s systems achieve exactly what AARON could not: they “improve” with use, absorb and spit out multiple distinctive styles, and often blur boundaries that have existed for millennia.

But as technology evolved, so did the conversation surrounding it — not always in productive ways. The AI art debate, instead of encouraging rational discussion of its future and implications, has devolved. The growing animosity between those who embrace AI and those who reject it has led to excessive internal scrutiny within the artistic community. This atmosphere not only suffocates creative expression. It also sidelines artists from shaping the future of generative AI, leaving decisions about its development and regulation to those who may not truly respect the arts.

Do androids dream of digital hues?: An overview of AI art

This perceived tension in the relationship between technology and art is nothing new. Art and machine have a complicated history, and almost every innovation has been met with resistance. Photography, digital painting and even printmaking are just a few techniques that were initially met with skepticism, seen as “threats” to traditional art when first invented; over time, each has found an accepted place in the artistic sphere.

Walter Benjamin, in his 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” described how mass reproduction strips art pieces of their “aura” — their connection to a particular moment in space and time. In many ways, AI revives similar deliberations about this loss, but it also exacerbates disconnection. It is generative, not just assistive, creating complete pieces with little human involvement. If mass reproduction leads to a loss of contact between the audience and the artist, AI dissolves the relationship between the “creator” and the artwork itself. In doing so, it challenges the very idea of human creativity, and the value art holds in contemporary society.

Unlike traditional tools, which are extensions of the artist’s hand, eye, mind or soul, AI often operates autonomously, producing results that may not have been visualized or intended by the human user. These are “black-box” systems, meaning the internal decision-making processes behind the conclusions that most models reach cannot be fully traced or understood, even by their makers. As users, all we can see is the input and output, and this lack of transparency is one of the reasons why AI art is so divisive.

Polarization is the defining feature of the 21st century dispute over AI art. For some, AI is a leap forward in the collaboration between human and machine, offering more possibilities, effective processes and a democratization of art. For others, it is a threat to the creative job market, and perhaps even to the very essence of originality. A myriad of ethical concerns about how models are trained back this concern, as some models scrape images from the internet without artists’ consent.

Yet ethical concerns are hardly the product of AI art. Photography, for example, was once prone to problems with misrepresentation and lack of consent, but as its presence grew, many photographers began to follow guidelines and policies to ensure the transparency and respectability of their work. While fundamentally different in the technical aspect, similar moral considerations apply to AI.

Technology itself has never been the problem. Rather, it is how humans use it and react to it. So while it is almost certainly true that generative AI is here to stay, that does not mean it is impossible to create a future where it fits ethically and constructively into the world of art.

The painted-over problem: How fear is the real threat to the creative world

In the age of the internet, the conversation around AI art has pivoted from a debate to a shouting match. From both supporters and critics, there is little room for nuance or understanding. It certainly does not help that proponents often downplay the concerns of artists’ fears, but it is also the case that the outrage surrounding AI art in the social media space increasingly deserves its common label as a “witch hunt,” where a single accusation of AI art use can mean the end of a career.

Some AI advocates voice loud yet fundamentally contradictory arguments in support of generative AI. For instance, while some claim that AI is “just another tool,” others argue that it learns the exact same way as human artists do. Such points make artists feel cornered and unheard, while also drowning out more rational arguments for generative technology use cases. But artists also respond in dismissive, derogatory terms, often tarring all AI-curious people with the same brush as “tech bros” and anti-art.

In taking this defensive stance, artists themselves could be the ones hit hardest by the anti-AI movement. A simple search on X (formerly Twitter), for example, yields pages of artists scrambling to defend themselves from accusations with screenshotted process photos or speedpaint videos. The bar for accusations is alarmingly low; anything that looks slightly out of place, unnatural or out of proportion can lead to a public call-out saying that a piece “looks AI-generated.” This does not only affect beginner artists, who make common mistakes that contain these “signs,” but also practiced artists who alter or abandon their artistic styles in order to avoid accusations of AI usage. Do these sentiments really protect art? One of the biggest criticisms of AI art is that it threatens artistic identity due to its ability to replicate styles. Yet the irony lies in how many artists are trading one form of identity loss for another as a defense mechanism. These allegations are not a move toward protecting the integrity of art, but instead an imposition of arbitrary boundaries that suffocate artistic expression. Additionally, this hostile environment discourages transparency that should come with ethical AI use, because artists who do use it in their process feel the need to hide it rather than acknowledge it. With more openness, users could choose to engage or disengage with AI-generated work based on their personal beliefs.

At the heart of this discourse is fear. Fear of job loss, fear of replacement and fear of the devaluation of one’s passion and hard work. Artists have valid concerns about how the rise of AI-generated work diminishes the demand for human-made art in some scenarios. While there is still a substantial demand for human artists, especially in more personal situations, AI is already replacing certain creative roles. In fact, a 2024 study from CVL Economics predicts that hundreds of thousands of creative jobs will be lost to generative AI from 2024-26.

The worst way to respond to fear is invalidation, and AI supporters and tech enthusiasts often dismiss artists’ concerns. The nature of social media increases this animosity, amplifying fear, misunderstandings and shame over necessary dialogue. And so, the uncomfortable truth is that how people are reacting to AI art is doing more harm to the art community than AI itself has the capacity to right now.

Reframing the picture: Why artists must play an active role in AI’s future

What even is art? At no point in history did this question have a simple or static answer. And, as AI challenges everything we know about art, the answer is more elusive than ever. In fact, there are too many unanswered questions that stem from generative AI, over ownership, credit and regulation just to name a few. If artists face AI with pure rejection in mind, if they refuse to answer these questions, those who value profit and personal agendas over creativity, like large corporations and policymakers, will answer them instead.

It is time to shift the conversation. There is no use in asking whether or not AI should exist in the artistic world. It already does, and it will probably never disappear. Cohen once said, “Art is not, and never has been, concerned primarily with the making of beautiful or interesting patterns. The real power, the real magic … rests not in the making of images, but in the conjuring of meaning.” If we do not want generative AI to erase the true value of art, the focus should be on how it should exist. Artists must be active participants, even leaders, in shaping this idea; legislation and industry standards should be developed with artists, not against them. Only empathy and sincere discussions can build an ethical future where AI and human creativity coexist.

The next chapter of generative AI and art is still being written — artists must be the ones holding the pen.