Below blinking skyscrapers, the streets of Beijing are crowded by businessmen pacing on phone calls, food stalls steaming with sesame aromas and children in the back seats of motorcycles on their way home from school. Two years ago, the hum of China’s cityscape was what Gaoxuan Tong (10) woke up to, fell asleep to and heard on his way to school. But when he moved to the United States 18 months ago, things could not have been more different.

“I came to America in order to pursue a better education,” Tong said. “In America, the academic pressure is not as difficult as in China, and students have time to do more extracurricular activities that are sometimes more helpful to [students] learning progress than doing homework. For instance, here in America, I have the opportunity to join clubs or start my own clubs … But in China, high school is more like just preparing for tests and doing homework.”

In 1986, the Chinese government enforced the Compulsory Education Law of the People’s Republic of China, implementing nine years of mandatory education. For students who do not score in the top percent of the Zhong Kao — a national exam taken at the end of middle school — government-funded education ends after ninth grade.

“I woke up at 6 a.m. every day, we finished class at 9:40 p.m. and slept at 11 p.m.,” Yutong Feng (9) said. “In China, the academic pressure is so hard, like everyone wants to be better and better than others.”

As a result, students experience heightened academic pressure and competition among peers.

“In Shanghai, [roughly] 35% of the students that attend the Zhong Kao will be eliminated,” Kimi Lu (10) said. “Only 65% [attend] high school.”

For the 35% of students who do not test into public high school, some choose to attend private schools or pursue vocational education at “professional high schools.” At the end of high school, Chinese students take the Gao Kao, the nationwide college entrance exam.

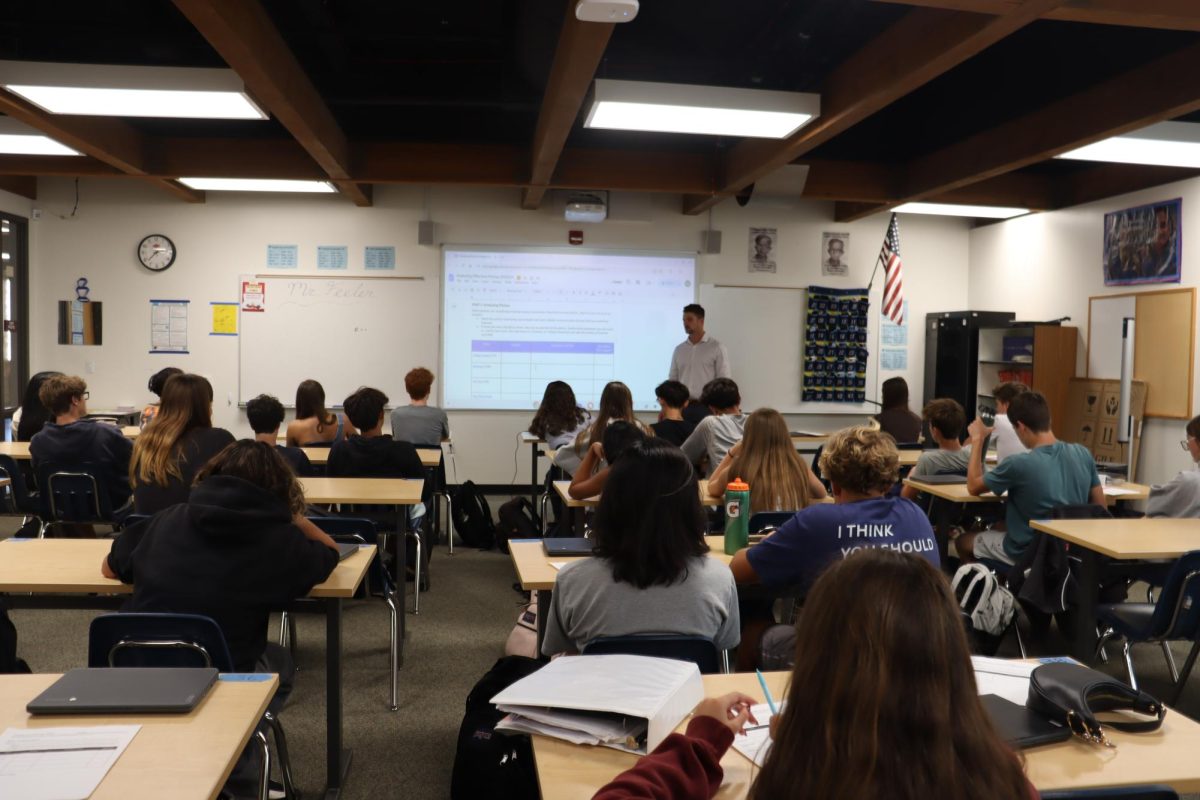

“In America, there are more choices,” Jo Zhang — the school’s AP Chinese Language as well as Chinese 1, 2, 3, and 4 teacher — said. “Preparing for the Gao Kao takes time from a child’s independent hobbies and interests. And in China, a lot of the material is dependent on memorization and repetitive practice. Some parents do not think this learning method is good for their children, even if it yields a high test score.”

In 2024, more than 13 million students in China took the Gao Kao, compared to the 3.37 million students that took the SAT and ACT combined.

“Over the past decades … there are too many college students graduating from universities,” Tong said. “But the issue is, society doesn’t need that great number of university students [because] there aren’t enough positions in Chinese society for these people. Basically, there is too much supply for university students, but there is not enough demand for university students in job applications. Chinese society needs more workers with specialized skills, such as fixing cars or cooking.”

Since arriving at San Diego from Shanghai, Lu has lived with three different host families. While some students study abroad via exchange programs, Lu is a transfer student.

“The first [host house] … I didn’t have my own room,” Lu said. “I shared my room with someone else, so I left that house in the first month. This semester, I had a new host family … but [there were] too many students in that house, so [my guardian] will probably, like, take me to school at 7:30 a.m. in the morning, and get home at 4 p.m. I didn’t want to do that… Then my mom found her friend [for me] to live in her house.”

Regardless of the country, transfer students worldwide face similar challenges: language barriers and adapting to social norms. Students that transfer later in their educational career juggle studies and learning English while adjusting to other factors in everyday life.

For Feng, one of her biggest fears was being isolated due to the language barrier.

“I thought I couldn’t make friends here,” Feng said. “I thought there were no Chinese people here — that people couldn’t speak the same language as me.”

Moreover, social norms in China vary from those in the U.S., affecting interactions with others.

“It appears that this is a very common practice here … if you’re walking [your] dog on the street and see someone pass by, you say ‘Hi,’” Tong said. “But Beijing is a very populated city, and there’s a lot of people on the street, so you can’t really say hi to everyone.”

Similarly, Lu was worried that no one would speak to him on his first day of school. In China, when “new students joined [his] class, nobody speaks to that new person.” But at TPHS, “people sometimes speak with those that are alone.”

“I think people here are just really friendly,” Lu said. “When I was on the [school’s] basketball team, everyone was willing to cheer. They cheer for every player who plays. In China, like, those good players are not willing to cheer for those not so good players … Every time I play on the court, they cheer for me.”