For elite athletes, sports are a 24/7 commitment. Passion for the game — whether keeping up with recruitment or honing drills — follows them the little time they have off field. With increasing pressure to withstand longer training and continue to perform at an intense rate, around 60% of high school athletes are often pushed to burnout, according to a study published in Health Psychology Research.

Adriana Adatiya (10) previously played field hockey at HTC Field Hockey Club on the High Performance team. She practiced “every single day,” 21 hours a week. That was until she hurt her ankle and tore a ligament while playing in England the summer before freshman year. After that, she developed chronic back pain. During freshman year, she played between JV and varsity for the school.

“Before, [field hockey] was my life,” Adatiya said. “That’s all I thought about. You know, when I went to sleep, when I woke up, that was something that I thought I was going to be doing in college.”

As a result of demand for improving performance, athletes push their bodies to a breaking point, often resulting in injury.

“When I injured my ankle, that was the moment where … everything kind of came to realization,” Adatiya said. “[It’s like] runners high, like, when you’re just so addicted to something. I was just in my high at field hockey … so I didn’t really realize I was burnt out until I was faced with an injury.”

It wasn’t until the injury that Adatiya realized her body took a toll from hours upon hours of training, and that she was physically burnt out, despite feeling a “runners high.” While some athletes experience burnout from injuries, in other aspects, it may also come from a mental shift towards the game. Burnout may be caused when joy from learning a new sport is overshadowed by validation to perform.

“Having too much on your schedule or … when the recruiting process gets too difficult or when coaches doubt you … led to my burnout,” varsity girls soccer captain, Annika Pallia (12) said. “When you’re at your peak … you have a lot of confidence. You know where you’re going to go. When you’re burning out … it’s just disappointing to know that if you were still at your peak, you would be going places further than you are.”

While Pallia began soccer when she was four years old, she played in the Elite Clubs National League for Legends FC San Diego until the end of her sophomore year, and currently plays in the Elite Clubs Regional League. To her, athlete burnout is the difference between “showing up to everything” and “knowing that there is going to be a stopping point soon.” But even as she registered this mental change, the decision to switch leagues was unexpected.

“I thought I was going to go play college soccer [and] live my life in soccer, and all of a sudden, it kind of randomly switched once I left the [ECNL] team,” Pallia said. “I realized [burnout] more gradually, but I realized it most when I made the decision to not play college soccer, and I just started taking soccer a lot less seriously.”

But the catalyst of athlete burnout is often overtraining without adequate recovery time, causing mental and physical exhaustion. Pallia noted that playing seven days a week while in the ECNL resulted in “hurt [to her] body.” During one match, Pallia sustained a spinal injury when a player fell onto her after both of them “jumped up for a header,” breaking Pallia’s fourth thoracic vertebra.

“Ultimately, the athlete that’s successful loves their sport and wants to train to become the best they can possibly be in their sport,” the school’s athletic director and track and field coach, Charlenne Falcis-Stevens said.

Nevertheless, for some athletes, love towards the sport translates to training day after day to focus on goals and push past limits, and as a result, burnout becomes an afterthought. As strong passion progresses without balance, overtraining causes decline in performance or joy towards the sport.

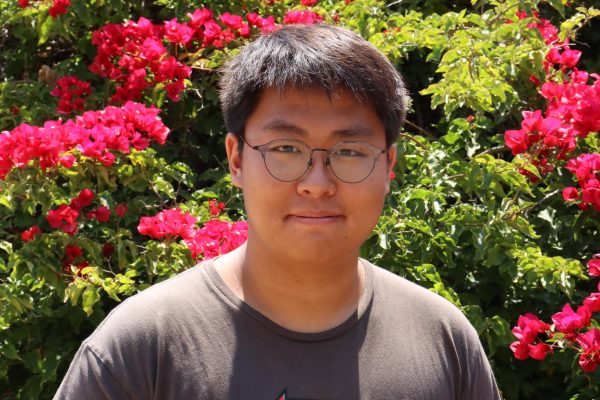

“I feel like, if you like the sport enough, you don’t want to burn out, and in that sense, you don’t foresee [burnout] or the consequences,” Evan Liu (10), who has been playing golf for 13 years, said. “You never want to put yourself in that frame of mind unless it just happens.”

Liu formerly experienced athlete burnout from “a ton of fatigue,” and “fluctuating” mood, which he often blamed on golf. Growing up playing golf for most of his life, Liu also shared that some athletes burn out as a result of pressure from parents.

“I know a lot of people who burn out just because they were forced to [play a sport] when they didn’t want to by their parents,” Liu said. “Being forced to do something you don’t want to do makes you associate whatever you’re doing with negative feelings, and that really repels you from [the] sport you’re playing.”

But no matter the reason, whether it be normalized overtraining to mental shifts to parental insistence, athlete burnout is common.

“As you get better at the sport, as you climb the ladder, in terms of … competition, you definitely deal with athlete burnout a lot more,” Adatiya said. “I know girls in college who have torn their ACL because they’ve just pushed their body so hard, and now that they’re competing at such a high level, they’re just more prone to athlete burnout.”

Both on and off season, coaches play a pivotal role in mentoring athletes. Falcis-Stevens believes that “encouraging the athlete to find ways to contribute to the program,” for example, including them in leadership roles decreases athlete burnout in season. Off season, she “encourag[es] athletes to participate in other extracurricular activities.”

“The early portion of the season is typically dedicated to learning the plays,” Falcis-Stevens said. “Once competition begins, the coach has to balance training with recovery to get the best out of their athlete or program.”

While athlete burnout pushes pause for many sports careers, it also serves as a semicolon, and marks a new clause to their life.

Post burnout, Pallia shifted focus to neuroscience, working an internships at Stanford Summer of Neurosciences and Sci-MI Neuroscience. According to Pallia, she plans on majoring in neuroscience and attending medical school. While taking a break from playing, Adatiya helps coach the U14 age group at HTC. In November, Adatiya looks forward to a surgery, and “hope[s] to return to field hockey in the spring.” Adatiya still aspires to play field hockey at the collegiate level. Liu, who has returned from burnout, currently plays in the American Junior Golf Association, traveling for tournaments twice a month during spring and summer.

“Managing your stress and reflecting and accepting and addressing it is important,” Liu said. “Most of all, try to find love for what you’re doing and joy in other parts of your life.”